Towards a Unified Field Theory of Summer Movies

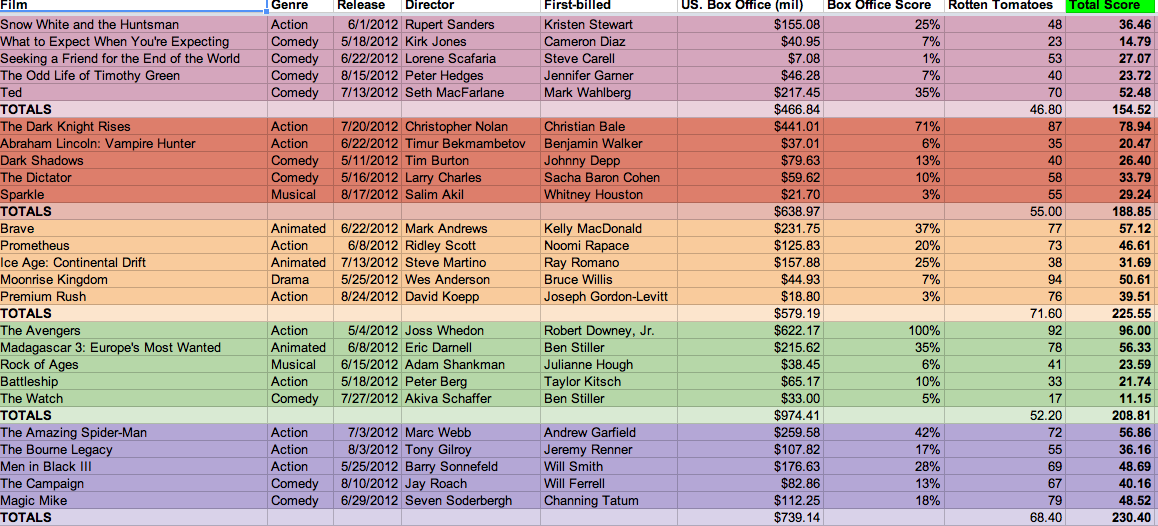

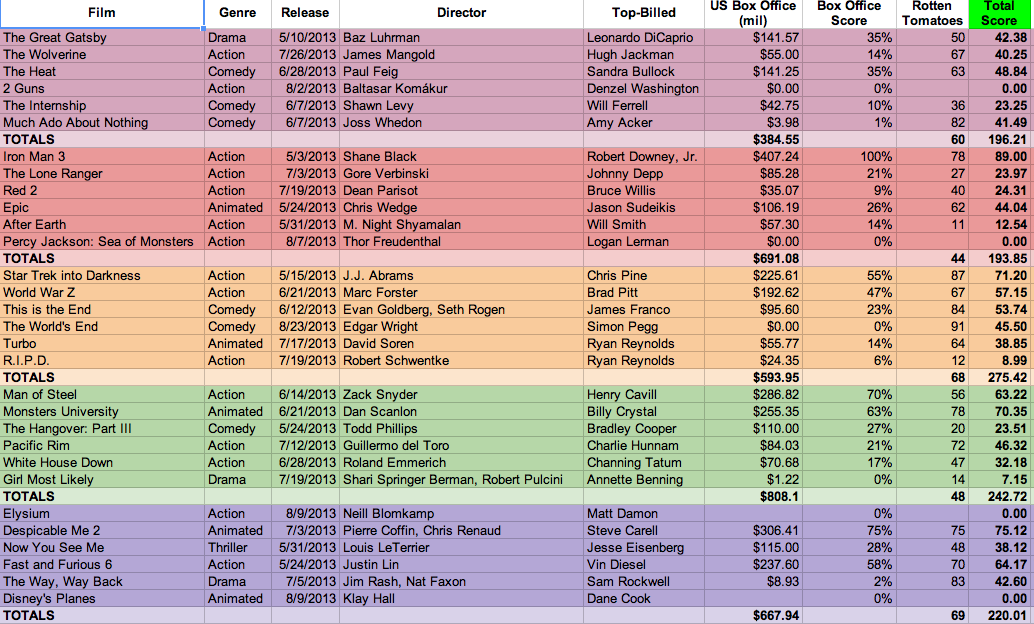

I'm a big fan of summer movie season. I've always enjoyed movies in general, but I've never been a capital-F "Film-lover" type. Sure, I appreciate a good arty or independent movie, but I've never taken a film class, nor have I seen Citizen Kane or Lawrence of Arabia. As such, I tend to see more movies in theaters in the summer than during the winter awards season (not to mention the difference in free time I have in the summer vs. December and January). I also, having stolen the idea from a friend, run a Summer Movie Draft, where five of us draft a "team" of summer movies. We then give each movie a score, based on how well it does at the box office, as well as its Rotten Tomatoes score. Below are two screenshots, one of last year's results, and one for this summer's contest.

All this to say that I spend a lot of time thinking about summer movies, especially the blockbuster types that tend to dominate the box office all summer. What surprised me this summer was the extent to which Man of Steel under-performed, despite its massive marketing push and pre-release buzz. Yes, it made a lot of money, and there's already a sequel planned, but the critical response was tepid, with only a 56% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Superman is clearly a well-known and beloved property, more so than the Avengers or Iron Man. So why did Man of Steel fail where those others did so well?

Most of the complaints about Man of Steel are with the film's third act, in which (spoiler) the entire city of Metropolis is leveled, mostly because of Superman. Geeks complained because this was out of character for Superman, who is known for defending as many civilians as he can, no matter what the cost to him. While there are legitimate concerns about what this means for Superman's character, the biggest problem is that this was simply a bad choice for the story. There was certainly plenty of action in the last 40 minutes of Man of Steel, and ostensibly that's what summer moviegoers are looking for. Yet for all the punching and flying and explosions and destruction, the finale of Man of Steel was undeniably boring, in a way that other explosion-packed finales are not.

We know Superman is essentially invincible, so any story featuring him must have stakes other than simply his survival. Superman and Superman II accomplished this by having Superman saving Lois Lane and other civilians, or by taking his powers away temporarily. In Man of Steel, director Zack Snyder and screenwriter David S. Goyer instead place the survival of the entire planet, and especially Metropolis, at stake. The problem is, we viewers cannot really comprehend or relate to planetary stakes. A good story can make us care about whether certain characters live or die, but an entire city or planet? That's more difficult.

The Avengers faced similar difficulties in last summer's blockbuster. Again, the entire planet was at stake, with the battle for its survival taking place in New York City. I think there are a couple reasons why the final act of The Avengers (mostly) works, where Man of Steel does not. One, the characters are more vulnerable. While we know intellectually that none of our heroes will die, they are all (except Thor) mostly human. Sure, there's a high-tech suit of armor and a giant green rage monster, but their basic humanity gives them a vulnerability that Superman lacks, at least in this most recent version. The team dynamic of the Avengers also keeps the action from getting stale. It's not a question of whether the superheroes will defeat the supervillain, but how they will do it. They even spend some time figuring out how to keep civilians safe, something Superman does not seem to consider. The stakes are still too high to be comprehensible, but the script keeps things interesting. Man of Steel is relying on the action sequences of one super-strong alien flying and punching another super-strong alien to be entertaining enough, but without any connective tissue, it feels rote.

There was a tweet from @FilmCritHulk the other day with an excerpt from Raymond Chandler that covers this ground much better than I could:

Action is not a substitute for the emotional response that moviegoers crave. With modern CGI, the action is easy. But relying on it at the expense of plot or characters isn't going to work, no matter how popular the superhero. And while my wonderful assistant principal may disagree, I don't think that Superman is being held to a different standard than the Avengers. The problems in Man of Steel are problems of execution. The best summer movies, the ones that appease both the hoi poloi and the critics, are the ones that understand Raymond Chandler's advice: the action has to be a means, not the end.